2021

[Fig.1]

Published in the Theatre, Dance and Performance Training Journal, edited by Independent Dance and Movement Training, Volume 12, Issue 2, June 2021

ISSN: 1944-3927

[BEGINNING]

Three years ago, I began a collaborative project, entitled Blackbird (2018), with dance-artist Katye Coe and filmmaker Charlie Cattrall. The premise was to create a dance work that explores the single dancer, She, embodying the power of her voice and limbs, and the voice and limbs of her kindred blackbird. The questions we asked ourselves as we sat in a dance-studio were: How can we embody the invisible relations between human and animal? How can one body perform the flock of many? How can Stefan’s voice, Katye’s movement and Charlie’s camera create a dance?

We spent time in fields and abandoned marshlands of the British West Midlands, home to the local blackbirds of the area. We listened to their singing at different times of day and we sat in silence where they slumbered. We walked into woodlands and swam down-river and drifted from one agenda to another. We found scores for animistic dancing in Ted Andrews’ seminal book Animal Speak (Andrews 1993) and used them to practice transfiguration. Katye would dance and speak her dancing, Charlie would film the dancing, and I would echo Katye’s words, sounds and movements while guiding her somatically and phenomenologically. Through my own choreographic mirroring of Katye’s somatic exploration, I would closely follow her felt-bodily stance as she travelled into the out-of-body realm, attempting to connect with the blackbird. In naming how she was feeling whilst moving, she would send me a lifeline to stay grounded in the physical world. In repeating her words, movements and sounds back to her, I would keep the portal between the here and there open. We both needed to be in continuous movement, conversation and relation, otherwise the connection would sever. Charlie would capture these fleeting moments, these spiraling dances and songs onto camera, our carrier bag of memories of animistic dancing now archived in a virtual hinterland. In hindsight I would describe the dance practice that we were developing as one that follows Ursula Le Guin’s Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction, a container of sensibilities and prompts, a library of somatic tools and exercises that could be invoked in a non-linear manner. I hope to offer some of these tools to you, reader, by asking questions in parallel to this recounting. I invite you to use these questions as prompts to explore your own somatic landscape and internal weathering and worlding.

How can you explore the edge where a tree meets the ground, the edge where you end, and the landscape begins? Hold the tree where the animal sleeps and then hold the earth that supports the soles of your feet. Hold the bird that has lost its wings.

Setting oneself the imaginative task of becoming a blackbird seemed to shift something in our nervous systems, bringing our perception of gravity, speed and orientation to the surface of our choreographic experience, as well as our embodied and projected tolerance for sensations belonging to that which is not human.

What would it be like if you touched into the edges of your capacity to tolerate interpersonal and interspecies difficulties? What would it be like to hold your judgement as well as your ability to discern, to hold others’ experiences within your own embodied nervous system, to hold empathy for yourself in the movement of dissonance? If in company, can you hold one another’s dancing as well as holding each other?

This choreographic learning is one that happens through collaboration and the implementation of another practice called Somatic Experiencing® (P. A. Levine). This latter is more commonly used as a form of trauma-therapy that attempts to create conditions and spaces of safety where a body can express its story through sequences of sensations. SE® aligns itself closely with older earthly practices of soul-retrieval, helping individuals find pockets of energetic life-force that had got frozen in the body’s memory field when that body's nervous system got overwhelmed with something traumatic. Energy that gets stuck in the body can fester until it forms into a spiritual wound over time, or sometimes referred to as a soul wound (Menakem 2017). In the therapy, the person is invited to track sensations within the body, noticing and naming what surfaces when asked: What is happening in your body right now? What do you notice in your body? What wants to happen next?

In this project, we combined our phenomenological ability to sense into spaces, histories and the fields that surrounded us, coupled with an awareness to track our bodily sensations while in movement. We sought for healing through movement. Healing in this instance means feeling that you are in the right place and of the right size, that there is a balance of give and take and that every next physical movement led to a stance that could sensationally be perceived as better and not worse. This choreographic learning was defined by the delicate edge between the spiritual and the danceable, that is, a generative and creative space where the personal could be used to access the otherworldly, and where the artistic/choreographic could become a methodology for healing the relationship between human and the other.

How might you hold love for the inanimate that lives on within you?

Dr. Peter A. Levine, the founder of SE®, describes trauma as a vortex formed in the side of a riverbank that has been struck by lightning. Every one of these vortex pools has an equal and opposite counter-vortex that forms within the river itself by the laws of physics, or as he calls them, the healing vortices. Sometimes we will hear the siren’s call and want to dive straight down into either of these swirling pools, to submerge ourselves in the depths of our pain or pleasure. We can do this unconsciously until we dissociate to another realm. At that point the magnitude, weight, and impact of those feelings may well have overwhelmed our body’s ability to tolerate sensation. Interestingly enough this metaphor stems from years of observing the ways in which both reptilian and mammalian animals react to danger, especially their physiological reactions when entering into states of fight, flight and freeze.

The knowledge of these animalistic orienting responses guided us in the way we understood the blackbird, the ways in which we attempted to expose our singular and collective nervous systems in the habitat of the bird. In becoming a bird, we had to configure our orientation response to sound, touch, sight, smell and a deeper somatic stance of what it means to resonate with another species.

This is where we introduced the SE® technique of pendulation, the act of swaying between the two vortices, physically and somatically (P. A. Levine 2010). You take a bit of activating material, you track it, you ask it where it wants to move to, and you attempt to discharge it, returning then to the resourceful place, the out-breath that allows you to drop a level energetically. The next time you visit that memory or sensation, and if you’re feeling it is safe and you’re ready, you might climb a step lower into the trauma-vortex, trying to discharge a bit more of what remains stuck. It’s a bit like peeling layers off an onion, with care and consideration, at just the right pace.

To work somatically in our case meant to fully embody the sensations that arose in the process of embodying the blackbird, and then sit with those sensations and allow ourselves to move through them.

![]()

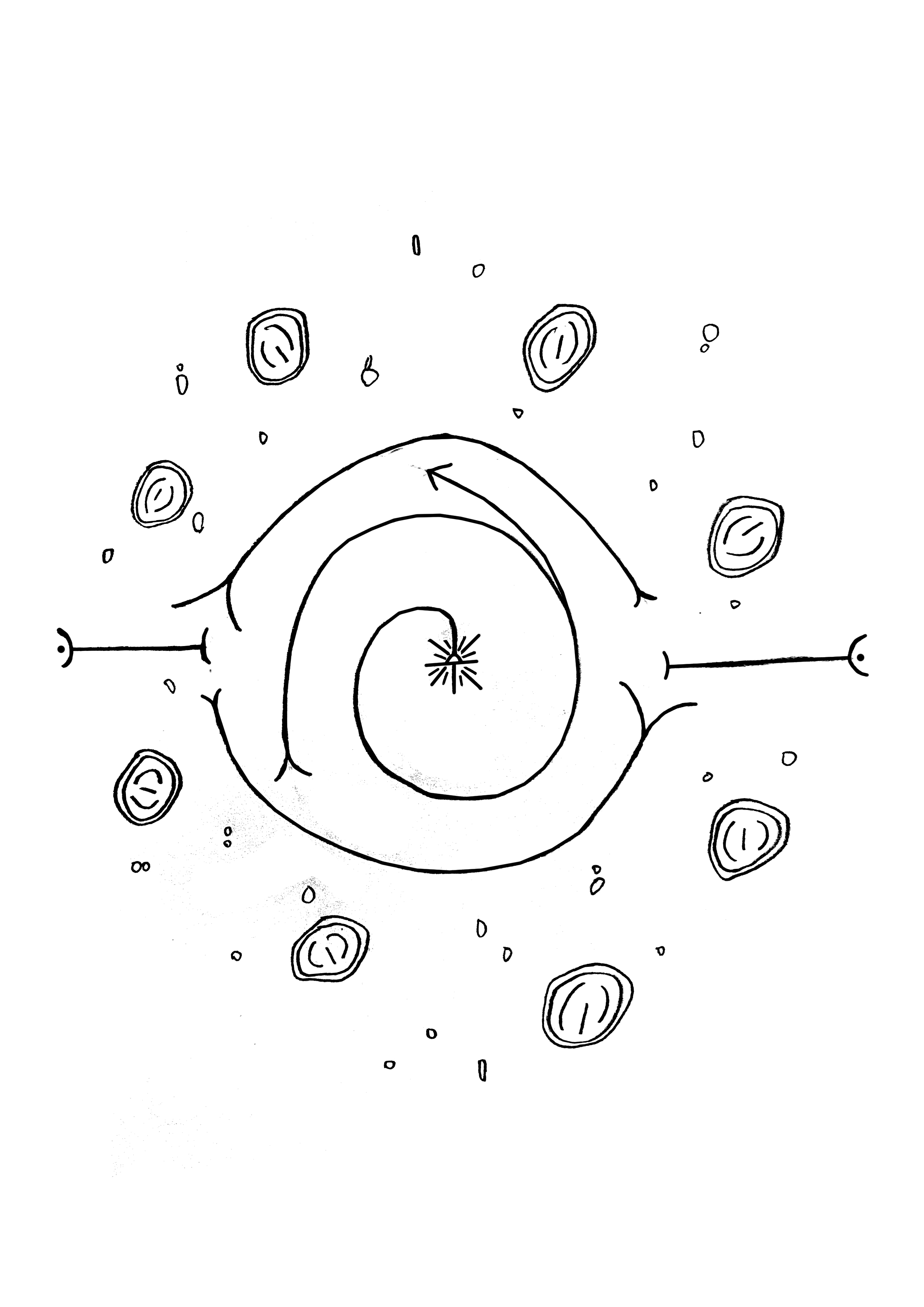

[Fig. 2]

My research has shown that it is the ability to tolerate both pain and pleasure which can lead to the autonomic nervous system restoring its own balance. That means to have a nervous system that is able to self-regulate and have a healthy orienting response when needing to fight, flee, freeze or be in social engagement. Rather than simply speaking of this pendulation in therapeutic jargon, what we explored in Blackbird was moving, speaking and sensing the choreographic journey from one vortex to the other. We attempted to first learn from the animal, and then learn from our own bodies. What emerged was a collective form of storytelling through dancing upon the peaks and troughs of a sin-curve, embodying what it means to seek shelter, to fly away, to play dead and to discharge. We made ourselves at home in a woodland meadow in Kenilworth, depicted in the last photograph, a place we would keep returning to practice this choreographic learning and practice making sanctuary with the blackbird (Akomolafe 2020).

The edge of disciplines is an edge that I want to draw your attention to. It is the physical edge of the spaces where dancing and other practices takes place. It is also the meta-edge of our conscious awareness as it extends into those dancing bodies other than our own. It is also the edge between a spiritual and an artistic intention that we set when we decide to dance. To hold that edge means to hold the capacity to be in multiple places at once, to hold information both in the neocortex and all throughout our Vagus Nerve, that is in places such as the belly, the heart and the lungs. This is the edge where you can learn how to build tolerance for that which does not belong to you, as you dance the story of another, sentient or otherwise.

This specific form of movement, combining animism with nervous-system tracking is a practice that can emerge in a space where the participants share a desire to move into something or somewhere, intosome shape, form or intent. It is movement that emerges out of necessity and intention, and within itself holds multiple biases and subjectivities: the fleeting, the random, the awkward, the tender, the nonverbal, the inarticulate and the ugly. It can stop all of a sudden, it can go on for hours and in one form of another it is labor that is paid. My contribution to this journal edition is one of choreographic knowledge-making that happens through practice. These reflections stem from several years of exploring how the Vagus Nerve aids us in moving in and out of the embodied, and how one can use that practice in different forms of spaces and semiotics. In our project, Blackbird (2018), our main ambition was to explore animal-human relationships through choreographic-therapeutic modalities. In this way we tested whether our dancing had any effect on our ability to practice affect, resonance and empathy with the blackbird and with any other animals we found in our immediate vicinity.

I leave you with a score on the facing page that you may interpret and use as you please. It is a drawn score that you can follow so that you too can develop your animal-speak. This score is intended as an interruption to your daily cycle, a digression that may interrupt the verbal and the articulate. I invite you to decide on a clear beginning and allow the ending to be felt, and everything in-between are prompts for your delight. Remember that the map is seldom the territory.

Find a clearing in the woods and decide on an animal that you want to make contact with.

Surround yourself with trees and decide how big your Field is, that is your container and capacity today.

Sense into the life of this creature, its daily cycle, its needs and desires, its predators, its preys and its friends.

Begin to move in a clockwise direction along the outer edge of your Field. Circle it three times.

Now begin to spiral towards the center of your field and then pause.

Begin to visualize the transformation of your body from human to animal.

Begin the transformation, starting with the soles of your feet, all the way to the top of your crown.

Sense. Dance. Scream. Sing. Track. Embody. Cry. Laugh. Keep on going until you feel you are done.

Reverse your transformation and then begin to spiral outwards to the outer edge of your Field once more.

Circle your way out of your Field three times and exit a different way than the one through which you arrived.

Keep on moving and do not look back.

[END]

Acknowledgements

The project described in this essai, Blackbird (2018), was created in collaboration with Katye Coe and Charlie Cattrall. The initial research and development (August 2018) was supported with funding by Culture Hub Birmingham. My translating of that research into written form was supported by the Society for Dance Research under the Ivor Guest Research Grant (December 2020).

Images Cited

Fig. 1, Blackbird. Rehearsals filmed in August 2018, featuring Katye Coe, Charlie Cattrall & Stefan Jovanović performing in Kenilworth Common. Filmed and edited by Charlie Cattrall. ãStudio Stefan Jovanović, Katye Coe, Charlie Cattrall.

Fig. 2, A Score for Animals. January 2021, drawn by Stefan Jovanović, interpreted from writings from Animal Speak (Andrews 1993). Studio Stefan Jovanović.

Works Cited:

Akomolafe, Bayo. 2020. “I, Coronavirus. Mother. Monster. Activist.” Scribd. 2020. https://www.scribd.com/document/466902311/I-Coronavirus-Mother-Monster-Activist-by-Bayo-Akomolafe.

Andrews, Ted. 1993. Animal Speak: The Spiritual & Magical Powers of Creatures Great and Small. Woodbury, Minnesota: Llewellyn Worldwide.

Levine, Peter. n.d. “Trauma Healing.” Somatic Experiencing - Continuing Education. https://traumahealing.org/.

Levine, Peter A. 2010. In an Unspoken Voice: How the Body Releases Trauma and Restores Goodness. North Atlantic Books.

Menakem, Resmaa. 2017. My Grandmother’s Hands: Racialized Trauma and the Pathway to Mending Our Hearts and Bodies. Central Recovery Press.

ISSN: 1944-3927

[BEGINNING]

Three years ago, I began a collaborative project, entitled Blackbird (2018), with dance-artist Katye Coe and filmmaker Charlie Cattrall. The premise was to create a dance work that explores the single dancer, She, embodying the power of her voice and limbs, and the voice and limbs of her kindred blackbird. The questions we asked ourselves as we sat in a dance-studio were: How can we embody the invisible relations between human and animal? How can one body perform the flock of many? How can Stefan’s voice, Katye’s movement and Charlie’s camera create a dance?

We spent time in fields and abandoned marshlands of the British West Midlands, home to the local blackbirds of the area. We listened to their singing at different times of day and we sat in silence where they slumbered. We walked into woodlands and swam down-river and drifted from one agenda to another. We found scores for animistic dancing in Ted Andrews’ seminal book Animal Speak (Andrews 1993) and used them to practice transfiguration. Katye would dance and speak her dancing, Charlie would film the dancing, and I would echo Katye’s words, sounds and movements while guiding her somatically and phenomenologically. Through my own choreographic mirroring of Katye’s somatic exploration, I would closely follow her felt-bodily stance as she travelled into the out-of-body realm, attempting to connect with the blackbird. In naming how she was feeling whilst moving, she would send me a lifeline to stay grounded in the physical world. In repeating her words, movements and sounds back to her, I would keep the portal between the here and there open. We both needed to be in continuous movement, conversation and relation, otherwise the connection would sever. Charlie would capture these fleeting moments, these spiraling dances and songs onto camera, our carrier bag of memories of animistic dancing now archived in a virtual hinterland. In hindsight I would describe the dance practice that we were developing as one that follows Ursula Le Guin’s Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction, a container of sensibilities and prompts, a library of somatic tools and exercises that could be invoked in a non-linear manner. I hope to offer some of these tools to you, reader, by asking questions in parallel to this recounting. I invite you to use these questions as prompts to explore your own somatic landscape and internal weathering and worlding.

How can you explore the edge where a tree meets the ground, the edge where you end, and the landscape begins? Hold the tree where the animal sleeps and then hold the earth that supports the soles of your feet. Hold the bird that has lost its wings.

Setting oneself the imaginative task of becoming a blackbird seemed to shift something in our nervous systems, bringing our perception of gravity, speed and orientation to the surface of our choreographic experience, as well as our embodied and projected tolerance for sensations belonging to that which is not human.

What would it be like if you touched into the edges of your capacity to tolerate interpersonal and interspecies difficulties? What would it be like to hold your judgement as well as your ability to discern, to hold others’ experiences within your own embodied nervous system, to hold empathy for yourself in the movement of dissonance? If in company, can you hold one another’s dancing as well as holding each other?

This choreographic learning is one that happens through collaboration and the implementation of another practice called Somatic Experiencing® (P. A. Levine). This latter is more commonly used as a form of trauma-therapy that attempts to create conditions and spaces of safety where a body can express its story through sequences of sensations. SE® aligns itself closely with older earthly practices of soul-retrieval, helping individuals find pockets of energetic life-force that had got frozen in the body’s memory field when that body's nervous system got overwhelmed with something traumatic. Energy that gets stuck in the body can fester until it forms into a spiritual wound over time, or sometimes referred to as a soul wound (Menakem 2017). In the therapy, the person is invited to track sensations within the body, noticing and naming what surfaces when asked: What is happening in your body right now? What do you notice in your body? What wants to happen next?

In this project, we combined our phenomenological ability to sense into spaces, histories and the fields that surrounded us, coupled with an awareness to track our bodily sensations while in movement. We sought for healing through movement. Healing in this instance means feeling that you are in the right place and of the right size, that there is a balance of give and take and that every next physical movement led to a stance that could sensationally be perceived as better and not worse. This choreographic learning was defined by the delicate edge between the spiritual and the danceable, that is, a generative and creative space where the personal could be used to access the otherworldly, and where the artistic/choreographic could become a methodology for healing the relationship between human and the other.

How might you hold love for the inanimate that lives on within you?

Dr. Peter A. Levine, the founder of SE®, describes trauma as a vortex formed in the side of a riverbank that has been struck by lightning. Every one of these vortex pools has an equal and opposite counter-vortex that forms within the river itself by the laws of physics, or as he calls them, the healing vortices. Sometimes we will hear the siren’s call and want to dive straight down into either of these swirling pools, to submerge ourselves in the depths of our pain or pleasure. We can do this unconsciously until we dissociate to another realm. At that point the magnitude, weight, and impact of those feelings may well have overwhelmed our body’s ability to tolerate sensation. Interestingly enough this metaphor stems from years of observing the ways in which both reptilian and mammalian animals react to danger, especially their physiological reactions when entering into states of fight, flight and freeze.

The knowledge of these animalistic orienting responses guided us in the way we understood the blackbird, the ways in which we attempted to expose our singular and collective nervous systems in the habitat of the bird. In becoming a bird, we had to configure our orientation response to sound, touch, sight, smell and a deeper somatic stance of what it means to resonate with another species.

This is where we introduced the SE® technique of pendulation, the act of swaying between the two vortices, physically and somatically (P. A. Levine 2010). You take a bit of activating material, you track it, you ask it where it wants to move to, and you attempt to discharge it, returning then to the resourceful place, the out-breath that allows you to drop a level energetically. The next time you visit that memory or sensation, and if you’re feeling it is safe and you’re ready, you might climb a step lower into the trauma-vortex, trying to discharge a bit more of what remains stuck. It’s a bit like peeling layers off an onion, with care and consideration, at just the right pace.

To work somatically in our case meant to fully embody the sensations that arose in the process of embodying the blackbird, and then sit with those sensations and allow ourselves to move through them.

[Fig. 2]

My research has shown that it is the ability to tolerate both pain and pleasure which can lead to the autonomic nervous system restoring its own balance. That means to have a nervous system that is able to self-regulate and have a healthy orienting response when needing to fight, flee, freeze or be in social engagement. Rather than simply speaking of this pendulation in therapeutic jargon, what we explored in Blackbird was moving, speaking and sensing the choreographic journey from one vortex to the other. We attempted to first learn from the animal, and then learn from our own bodies. What emerged was a collective form of storytelling through dancing upon the peaks and troughs of a sin-curve, embodying what it means to seek shelter, to fly away, to play dead and to discharge. We made ourselves at home in a woodland meadow in Kenilworth, depicted in the last photograph, a place we would keep returning to practice this choreographic learning and practice making sanctuary with the blackbird (Akomolafe 2020).

The edge of disciplines is an edge that I want to draw your attention to. It is the physical edge of the spaces where dancing and other practices takes place. It is also the meta-edge of our conscious awareness as it extends into those dancing bodies other than our own. It is also the edge between a spiritual and an artistic intention that we set when we decide to dance. To hold that edge means to hold the capacity to be in multiple places at once, to hold information both in the neocortex and all throughout our Vagus Nerve, that is in places such as the belly, the heart and the lungs. This is the edge where you can learn how to build tolerance for that which does not belong to you, as you dance the story of another, sentient or otherwise.

This specific form of movement, combining animism with nervous-system tracking is a practice that can emerge in a space where the participants share a desire to move into something or somewhere, intosome shape, form or intent. It is movement that emerges out of necessity and intention, and within itself holds multiple biases and subjectivities: the fleeting, the random, the awkward, the tender, the nonverbal, the inarticulate and the ugly. It can stop all of a sudden, it can go on for hours and in one form of another it is labor that is paid. My contribution to this journal edition is one of choreographic knowledge-making that happens through practice. These reflections stem from several years of exploring how the Vagus Nerve aids us in moving in and out of the embodied, and how one can use that practice in different forms of spaces and semiotics. In our project, Blackbird (2018), our main ambition was to explore animal-human relationships through choreographic-therapeutic modalities. In this way we tested whether our dancing had any effect on our ability to practice affect, resonance and empathy with the blackbird and with any other animals we found in our immediate vicinity.

I leave you with a score on the facing page that you may interpret and use as you please. It is a drawn score that you can follow so that you too can develop your animal-speak. This score is intended as an interruption to your daily cycle, a digression that may interrupt the verbal and the articulate. I invite you to decide on a clear beginning and allow the ending to be felt, and everything in-between are prompts for your delight. Remember that the map is seldom the territory.

Find a clearing in the woods and decide on an animal that you want to make contact with.

Surround yourself with trees and decide how big your Field is, that is your container and capacity today.

Sense into the life of this creature, its daily cycle, its needs and desires, its predators, its preys and its friends.

Begin to move in a clockwise direction along the outer edge of your Field. Circle it three times.

Now begin to spiral towards the center of your field and then pause.

Begin to visualize the transformation of your body from human to animal.

Begin the transformation, starting with the soles of your feet, all the way to the top of your crown.

Sense. Dance. Scream. Sing. Track. Embody. Cry. Laugh. Keep on going until you feel you are done.

Reverse your transformation and then begin to spiral outwards to the outer edge of your Field once more.

Circle your way out of your Field three times and exit a different way than the one through which you arrived.

Keep on moving and do not look back.

[END]

Acknowledgements

The project described in this essai, Blackbird (2018), was created in collaboration with Katye Coe and Charlie Cattrall. The initial research and development (August 2018) was supported with funding by Culture Hub Birmingham. My translating of that research into written form was supported by the Society for Dance Research under the Ivor Guest Research Grant (December 2020).

Images Cited

Fig. 1, Blackbird. Rehearsals filmed in August 2018, featuring Katye Coe, Charlie Cattrall & Stefan Jovanović performing in Kenilworth Common. Filmed and edited by Charlie Cattrall. ãStudio Stefan Jovanović, Katye Coe, Charlie Cattrall.

Fig. 2, A Score for Animals. January 2021, drawn by Stefan Jovanović, interpreted from writings from Animal Speak (Andrews 1993). Studio Stefan Jovanović.

Works Cited:

Akomolafe, Bayo. 2020. “I, Coronavirus. Mother. Monster. Activist.” Scribd. 2020. https://www.scribd.com/document/466902311/I-Coronavirus-Mother-Monster-Activist-by-Bayo-Akomolafe.

Andrews, Ted. 1993. Animal Speak: The Spiritual & Magical Powers of Creatures Great and Small. Woodbury, Minnesota: Llewellyn Worldwide.

Levine, Peter. n.d. “Trauma Healing.” Somatic Experiencing - Continuing Education. https://traumahealing.org/.

Levine, Peter A. 2010. In an Unspoken Voice: How the Body Releases Trauma and Restores Goodness. North Atlantic Books.

Menakem, Resmaa. 2017. My Grandmother’s Hands: Racialized Trauma and the Pathway to Mending Our Hearts and Bodies. Central Recovery Press.